One thing that encourages me about our continuing discussion of what to do regarding our opioid “problem”– more and more people seem aware that all this has happened before.

One thing that encourages me about our continuing discussion of what to do regarding our opioid “problem”– more and more people seem aware that all this has happened before.

Drug epidemics, I mean. This one may have lasted longer and done more damage than most, but that’s a bit like comparing Vietnam to Korea. They’re different, sure, but they’re both wars.

This is the fifth epidemic I’ve observed since entering the field of addiction treatment, largely by accident, in the late 1960’s. The “lead” drugs do change– those being the ones that draw the most attention– but there’s always a lead drug. Sometimes it’s heroin, sometimes prescription drugs, sometimes cocaine, or crack cocaine, or methamphetamine, or PCP or Ecstasy or synthetic cannabis. But it’s always something.

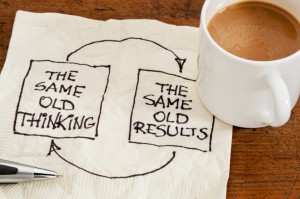

The sheer repetitiveness of epidemics can be hard to fathom. Seems like as soon as one tapers off, another begins to emerge. Weirdly, despite our recent experience, we’re still not adequately prepared when it does.

I can’t recall where I first heard this next bit, but I suspect it may have been from David Smith of the Haight-Ashbury Free Clinic. If I’m wrong, somebody please correct me. For me, this model still works as a way of understanding the cyclical nature of drug epidemics.

The elements that are required to foster an epidemic are:

An increase in availability of a drug

After all, the drugs we’re talking about are ‘self-reinforcing’, which means there’s something about the drug itself– its pharmacological properties– that leads people to want to repeat its use. I’m not necessarily talking about powerful drug hunger (that usually comes later), but there’s enough pleasure associated with the experience to make it popular. Word of mouth takes over from there, whether in the parking lot at a high school or late at night in a college dorm or on the street among dealers and users. The drug can be something new, or more often, something “new-old”, meaning it’s been modified in some way, the way crack is a modified form of cocaine.

At the outset, promotion beyond simple talk isn’t really needed. If the drug sounds desirable enough, people will seek it out. And tell their friends. Even it’s not that easy to get, customers will find a way.

Decrease in price and increase in potency

This is an early result of competition between suppliers for the drug dollar. Some suppliers are already in place and simply looking to add another star to their product line– the way a drugstore would put up a display titled “As Seen on TV”, or a grocer would advertise a new line of organic produce. Even if it’s not your primary revenue source, why not add it? it’s all revenue.

But as a drug becomes more popular, its price is likely to fall, again due to increased competition. That actually broadens the customer base, in much the same way that cheap computers and phones expanded access to the Internet and drew in new users. If the supplier can’t attract enough market share with price cuts– and there’s an obvious limit to that– they can always look to improved quality. In the case of abused drugs, that means increased potency. Users really value that as their tolerance elevates.

Of course, you can also jack up potency with adulterants– like fentanyl. The market’s already well-established by that point, so in practice a supplier is simply feeding it in a way that optimizes his profit. As they say in Texas, by that point, it’s just bidness.

Public overconfidence in the safety of a drug

This should get more attention that it does. It illustrates one of the original examples of fake news. The usual source– “experts” who assure the public that drugs are safer than previously thought, and the media (all forms) that uncritically publicizes those claims in search of readership. I know it’s not popular to bring this up, but I can’t help wondering if we’re not seeing some of the same with cannabis. Its potency seems to be on the increase even as it’s portrayed by the media as something of a medical miracle.

Increased competition among suppliers (drug wars)

This is a later stage phenomenon, when criminal gangs have come to dominate the supply chains, and they’re forced to war over territory and market share. It’s happening now in Mexico and probably in certain big US cities. As Sam Quinones explains so well in his prizewinning book Dreamland, that’s what attracted traffickers to rural communities in the first place — absence of competition from established criminal gangs. Dealing with rural users was like delivering pizza to an address in the suburbs. Transactions were conducted quietly in fast food parking lots.

I’d argue that essential to prediction (and perhaps even prevention) of future epidemics would be, at minimum, the following:

A rapid-response early warning network: We already have this to some extent, but my impression is it hasn’t adapted to the vast growth in newer communication channels such as the Internet and social media. There’s now a huge user community out there that deserves attention. This should be both a national and a local effort, because drugs don’t respect geographical boundaries.

Continuous monitoring and reporting on price and potency. Again, monitor electronic communication, not just street talk. If you think the Russians are experts at propaganda, you should check out the drug business. It’s hype in action.

Be skeptical— perhaps even suspicious– of claims, expert and otherwise, of safety and efficacy for drugs where research and clinical evidence are still in question. Experience teaches that such claims often fall apart with the passage of time. Yet they’re used to convince the public that trying Drug X, Y, or Z would be a great idea — or at least not a real risky one.

In a way, we all suffer from memory deficits when it comes to recall of past drug epidemics. It reminds me of the addicts who convince themselves to return to use in the hope that somehow, despite all the pain and shame of the past, things will turn out different.

It’s the sort of error that a society can’t afford to make. Because once the ball starts rolling, we’re not able to stop it. That turns us all into observers, helplessly watching things take their course.