This recent research study seemed to get an inordinate amount of publicity, mostly because it gave people something to argue about.

This recent research study seemed to get an inordinate amount of publicity, mostly because it gave people something to argue about.

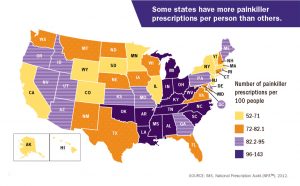

The researchers discovered a correlation between unusually high rates of opioid prescriptions in a region or community, and the percent of voters who voted for Trump in 2016. Competing explanations were offered. One was that these areas, mostly Appalachia and the South, were hardest hit by economic and social problems, and therefore most responsive to a message of political change.

The other explanation was that people who vote for Trump were drug-addled.

I’ll stay away from that debate, because what caught my eye was a comment by the principal researcher. He speculated that chronic opioid users would naturally be “stoned and unlikely to have voted at all.” Most Americans don’t vote– it’s a national disgrace — but the image of the addict sitting around stoned, doing nothing, enjoying the high, isn’t accurate. The reality: much of an addicted user’s day is filled with anxiety about where to obtain future doses.

The elevated tolerance of the opioid user dictates the amount required to stave off the onset of painful withdrawal. It can be a very high dose. When Bret Favre reports having taken fourteen Vicodin at a time, prior to playing an NFL game, I find that believable. He’s doing it not to get high but to function. In his case, to win a pro football game in front of thousands of spectators. Without opioids, he can’t do it. He’d be too sick from drug withdrawal.

We can imagine how important the role of opioids would be in his daily life. If continued access to opioids ever shows up on an election ballot, he’ll be first in line to vote. Anything that threatens his supply directly threatens his ability to work, care for his family, function at the most basic level.

That’s some way to live, huh? You can see why celebs with drug problems go to great lengths to cultivate physicians who are willing to assure them of continuing access to drugs. And willing to pay for it. I recall one pop music performer who budgeted in the mid-six figures for drugs to take along on an extended road trip. Drugs cost a lot more away from home, where you don’t have a local connection.

Nowadays, most folks who wind up in opioid treatment insist they started with prescribed medications. Only later did they turn to the street. The reason’s the same: because at some point, heroin becomes the cheaper, more available option.

As with most addictions, patients can be extremely reluctant to acknowledge their problem. As one put it, “I’m a pain patient, dammit. I’m not an addict.” To which another group member responded: “Why can’t you be both?” You can, of course. It’s something of a natural match.

The current opioid epidemic arose as a result of changes in medical practice promoted by pain physicians and Big Pharma firms with products to sell. The typical patient is older, has multiple medical and/or mental health problems, and exhibits less history of antisocial (criminal) behavior than street users of the Sixties and Seventies. Accordingly, they’re often more likely to respond to treatment, provided they can get it.

Unfortunately, access to treatment is far from guaranteed. They may have voted for the President, but there’s a lot more his Administration could be doing to help.