In clinical trials, medications show promise for treating heroin addiction

The above-linked article discusses the results of a clinical medication trial that compared the effectiveness of extended release naltrexone (monthly injection) to buprenorphine, a daily opioid substitute. The findings have apparently spurred some debate, although I found them to be predictable. Both medications improve rates of abstinence from heroin and other opioids. The surprise was that naltrexone injections appeared statistically superior in that respect.

The above-linked article discusses the results of a clinical medication trial that compared the effectiveness of extended release naltrexone (monthly injection) to buprenorphine, a daily opioid substitute. The findings have apparently spurred some debate, although I found them to be predictable. Both medications improve rates of abstinence from heroin and other opioids. The surprise was that naltrexone injections appeared statistically superior in that respect.

It’s not a big advantage — 52% for buprenorphine, vs 56% for Vivitrol. Also, because the naltrexone medication requires detox prior to induction on maintenance, 25% of subjects drop out at that level. That’s far higher than simply switching to Suboxone. It all makes a difference in practice, especially because naltrexone injections are so costly. Payers need a justification for the added expense.

Which leads me to the next question: why are naltrexone injections so costly? Given that naltrexone itself has been around for years and is widely available in other forms at much lower cost?

I suspect corporate profits have something to do with that.

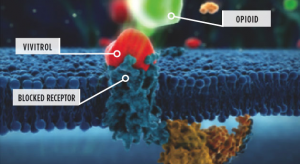

As for the different outcomes, I thought that was probably due to the different approach each takes to its goal. Naltrexone interferes with heroin as it binds to opioid receptors. That means the user doesn’t get the rewarding effects s/he seeks. Buprenorphine and methadone are themselves opioids and seek to reduce the user’s desire/need for heroin by satisfying it. Given the dramatic differences between individuals in terms of tolerance and withdrawal, that might actually be the bigger challenge.

Traditionally, the problem for antagonist medications is compliance — convincing people to stay on the medication. Monthly injections have a natural advantage. And there are implants in development that may extend effectiveness up to six months.

The opioid maintenance patient knows that without the medication, withdrawal discomfort will quickly follow. That’s a real incentive to comply. If the individual does suspend taking the medication, however, regardless of reason, estimates of return to heroin are in the 80% range, and up.

The study suggests that patient satisfaction ratings were superior for those on naltrexone. That counts in terms of compliance, too.

So it does sound as if there are good reasons for adding naltrexone to the therapeutic arsenal. We need a practical decision tool to help physicians decide which one is likely to work best for a particular individual.

As an aside, I’ve long been aware that many patients on both types of medication-assisted treatment continue their substance use. The incentive to add other intoxicants is strong. Alcoholic drinking is common in opioid maintenance programs, as is use of benzos, stimulants, and cannabis. I’ve certainly heard reports of continuing alcohol and drug use among naltrexone patients, as well.

Be wary of exaggerated claims of effectiveness. The medication aids recovery, but much work remains. Close monitoring can make a positive difference in outcome. So can cognitive therapy and peer support.

What I would hope to avoid: reliance on a treatment where the client’s substance use decreases but doesn’t stop. Or perhaps stops for a while, then starts up again. With the patient managing, as addiction patients have been known to do, to avoid discovery.

When that happens, we may have achieved a lot in terms of harm reduction, particularly overdose, but not much in terms of lasting behavior and lifestyle change.

Without that behavior change, I suspect retention in treatment will continue to be a problem. So will relapse.