I was pleased to hear that the folks at IRETA— the Institute for Research, Education and Training in Addictions– have taken on a project I find of particular interest: The value and viability of providing more intensive treatment services in a methadone maintenance program.

I was pleased to hear that the folks at IRETA— the Institute for Research, Education and Training in Addictions– have taken on a project I find of particular interest: The value and viability of providing more intensive treatment services in a methadone maintenance program.

They’ve partnered with Southwest Behavioral Health Management and Foundations Medical Services, LLC (FMS) on a two year project that began about 9 months ago. So far, things appear to be going well. If that holds, I’d hope the final product would be available for replication in other opioid treatment settings.

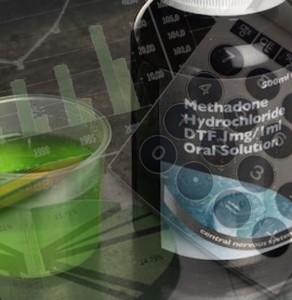

Currently, the regular opioid treatment program (OTP) schedule includes two and a half hours of counseling every month– one hour with a primary clinician, plus 90 minutes of other activities. The existing program offers considerable flexibility. A client struggling to adapt to medication could attend a special activity.

What hasn’t been readily available is a cohesive group therapy where 10-14 clients could bond with one another around their shared recovery. That’s the basic unit of most drug-free approaches. What would happen if it could be incorporated into the OTP curriculum?

The FMS and IRETA staff decided to pilot a closed, 12 week group experience built around structured Cognitive Behavioral Therapies (CBT). Some of the activities were based on William White’s Recovery Oriented Methadone Maintenance, available here for free.

A single group facilitator is responsible for the entire three months of the program. Client progress is tracked. Participants are asked to rate each session, and their input is then aggregated for review– a real asset for program improvement, but one that’s sometimes overlooked.

The plan is to add other layers of programming as the project matures. A weekly alumni-style group for graduates, for example. And eventually, an IOP component for those who struggle and require added structure to maintain recovery.

The group has only been in operation a few months, but some issues were immediately apparent. The population of addicted people in the group have experienced considerable personal loss, both recent and in the remote past. They’re in need of grief and bereavement counseling. Likewise, there’s a continuing demand for coping skills education: Anger management, stress reduction, conflict resolution, etc.

Oh, and help learning to manage craving. That’s almost universal. Even with medication, participants report periods of drug hunger that, left unaddressed, could quickly sabotage recovery.

As far as outcomes, the program team is focused on the harm reduction measures common to methadone maintenance: Days opioid-free, episodes of other substance use, arrests/criminal activity, high risk behaviors such as IV use. But the therapy itself is recovery-focused.

There’s been much concern about the spread of opioid use to rural environments that rarely if ever saw the problem in earlier decades. This project should provide some insight into treatment of that population. Currently, the group is predominantly white and female.

We may follow up later to see how the experiment is progressing. With so many Americans on maintenance– I’m told more than 350,000, and growing– it’s bound to be worth our attention.